In Flanders Fields

Everybody knows the iconic poem of WWI, In Flanders Fields:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

The author, John McCrae, a Canadian who died on the Western Front in 1918, wrote it after one of his friends had been killed in Ypres in 1915. I’m really bad at reading poetry, but online there are plenty of dramatic readings. Here’s one by Leonard Cohen. There are also numerous musical renditions, like this one by Sabaton, which I actually like very much. While I normally use Sabaton (or Motörhead, or Rammstein) to speed up the process of grading, their version of In Flanders Fields wouldn’t serve that purpose—because you want to stop and listen. I find this poem, in whatever form, really moving. I’m sure that I’m not the only one, but originality has never been my thing.

Probably everyone has seen pictures of the Western Front: the mud, soldiers blinded or killed by gas, the landscape bare of trees and full of craters. Everyone has heard of the 20,000 killed during the first day of the Somme. Imagine the horror of jumping over a trench, knowing that you’d very likely be shot. Imagine the horror of being bombed for days while sitting in a dugout, hoping to survive, but knowing that as soon as the bombs stop falling, people trying to kill you will be running towards you. That is, if their bombs have managed to cut the wire—because otherwise, it’s their turn to be shot while stuck there. The horror. For everyone involved.

Movies like 1917 or All Quiet on the Western Front make you really feel the horror of the Western Front. Books like Remarque’s Im Westen nichts Neues or Robert Graves’ Goodbye to All That have the same effect, but ridiculously, what makes it feel most visceral to me is the ending of the comedy series of Blackadder Goes Forth.

Something all those depictions of World War I have in common is that there is no winner. Not even locally. Blackadder jumps over the top, and you know nothing changes—except that most likely, they will die. The scene ends as they enter the enter no man’s land. Four million soldiers died on the Western Front.

What drove these people to jump over the top? Evidently, there was discipline; there were soldiers shot for desertion; there were large mutinies. But a lot of people did jump over without Stalinist NKVD battalions shooting those who refused. Blackadder isn’t forced to do it at gunpoint. Whether it was a sense of duty or comradeship, there’s something undeniably heroic in it. Maybe the whole thing was pointless. Maybe the generals were truly donkeys leading lions. Maybe the soldiers jumped over because they’d been brainwashed by militarism and imperialism. But there’s something undeniably heroic in that.

Yesterday was Armistice Day, a holiday here in France. There’s a minute of silence, and flowers are placed at the thousands of monuments to the fallen of World War I. In the UK, Canada, and probably elsewhere in the “Dominions,” people wear the red poppy. The French version is le bleuet de France, but I’ve never seen anyone wear one on the street. In Canada, I always found the red poppy very moving. It seemed to me that, beyond formally honoring the war dead, it was a symbol through which people showed each other that something like society exists—or rather, that it’s not just a collection of individuals.

Maybe I was mistaken, or naïve, and once those directly affected by the war disappeared, the only content of the red poppy was as a symbol of jingoistic fervor. Maybe things have also changed in Canada in the last 13 years. In the UK, it seems the red poppy is now very controversial, with right-wing politicians using it as a weapon. They evidently do it for political gain—to score cheap points, to label their opponents—but if you look at what they say, it’s clear they’re destroying the symbol. If the red poppy becomes associated with Farage, a lot of people will refuse to wear it. This evidently happens. Franco exploited and devalued all sorts of symbols in Spain, and when, during the 2010 World Cup, Alexandra got me a Spanish flag and I told my mother, she reacted as if I’d told her I’d found a kilogram of cocaine in the apartment.

Finally, one could argue that the red poppy just celebrates the mindless and barbaric slaughter of millions—millions who were brainwashed with nonsense like “for King and country.” In some sense, that feeling resonates with me. On the other hand, I’m pretty sure many civilians in Ukraine are really grateful for what the soldiers are doing at the front.

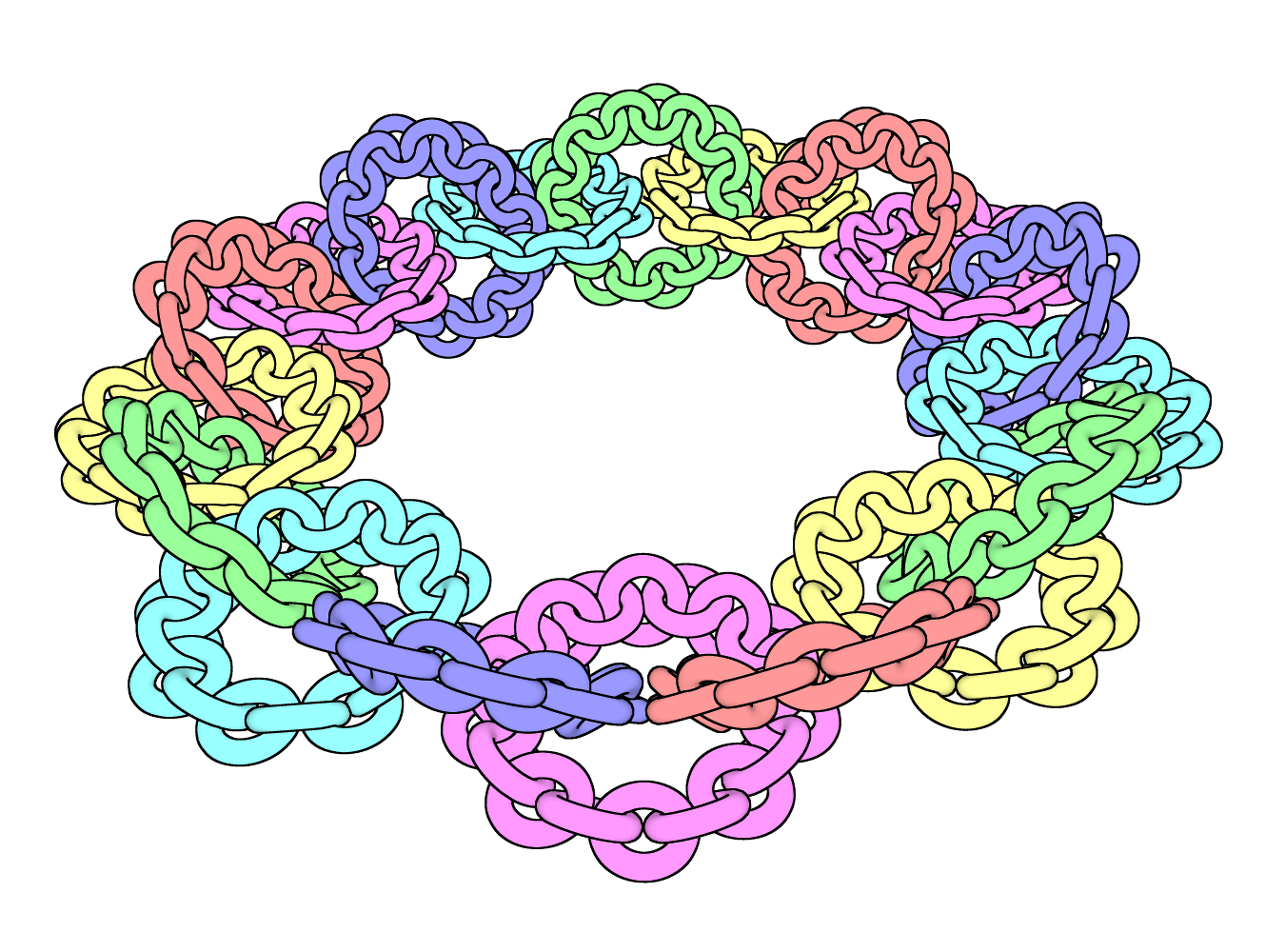

Why is that picture up there? The picture, taken from Wikimedia Commons, represents one of the stages of the construction of Antoine’s necklace, one of my preferred mathematical objects. Louis Antoine was a French mathematician, professor at my department. After being blinded in 1918, he followed Lebesgue’s advice and worked on low-dimensional topology—apparently because it’s something that can be done without sight. This rationale, and in fact the whole story, makes Antoine’s necklace even more amazing and mysterious to me.