A dark puzzle

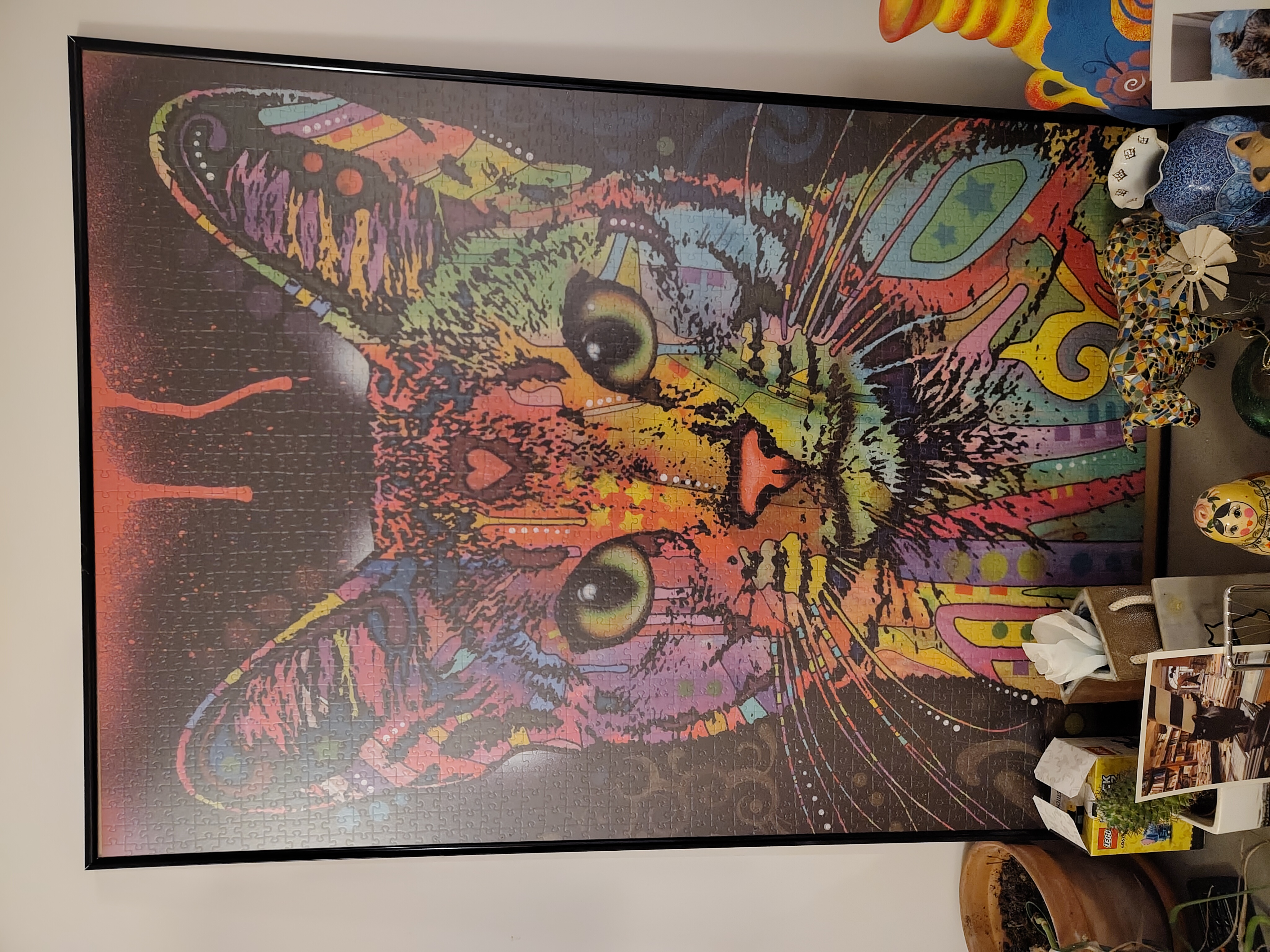

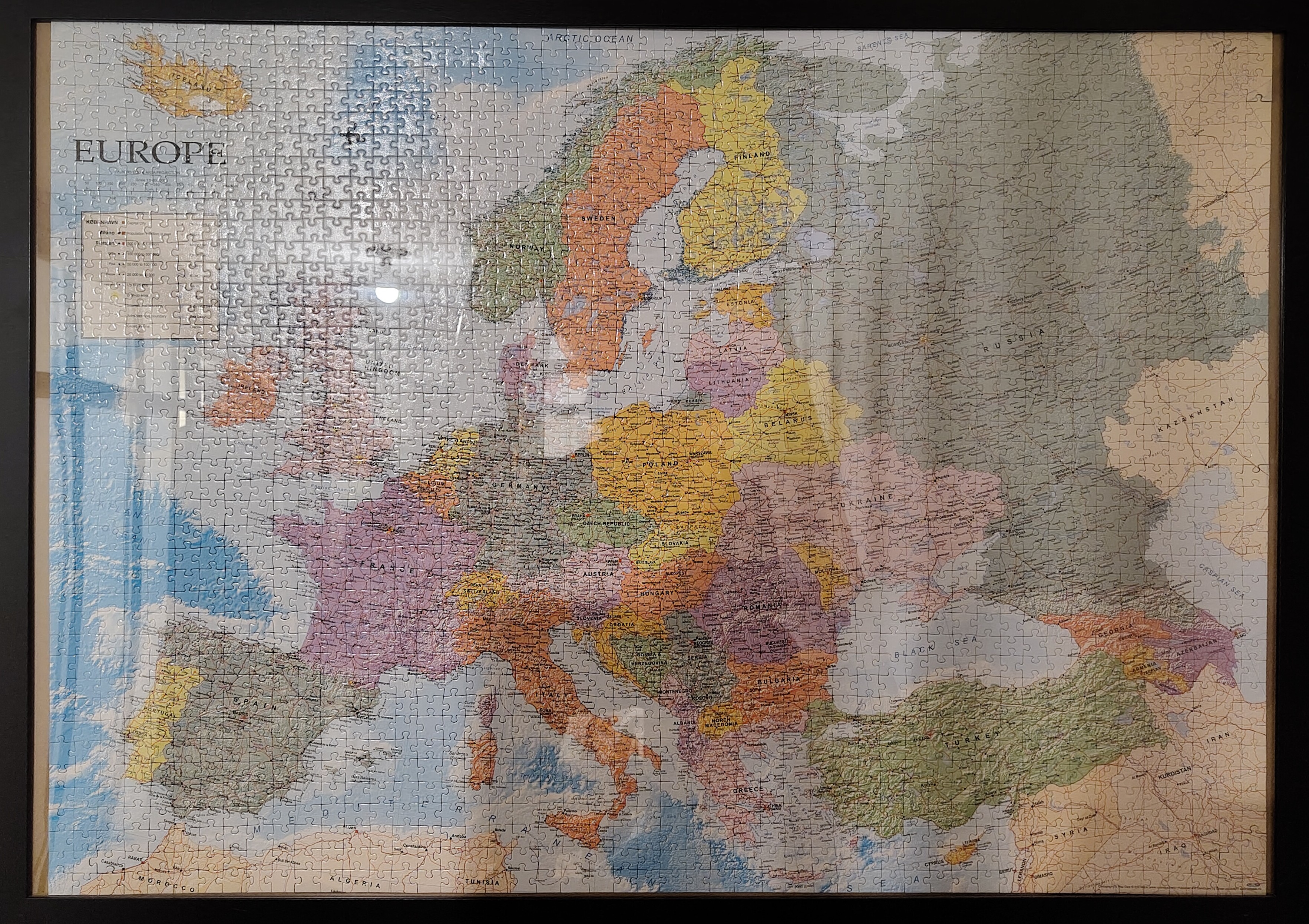

During COVID, I discovered that I like making puzzles. Actually, it might have happened a bit earlier, during that period of boredom after the being was born, when one spent lots of energy doing nothing and watching her do nothing. I like large puzzles—puzzles that take days to finish. With the local cat infestation, the logistics are not easy, and when I make one—it has been a long time—the table is occupied, and we might be forced to eat on the couch, almost directly from the pot because all the bowls are filled with pieces, mostly sorted after their color. As you see in the picture on the right, I sometimes frame the finished puzzle, thus acquiring another object that will be covered in dust. And cat hair. Anyway, while that cat puzzle is truly beautiful, the puzzles I find most satisfying are those that depict a map.

I always liked maps. As a kid, I drew and collected lots of them. I still have some. I invented a completely idiotic game, a paper version of computer strategy games like Civilization. The board consisted of enormous, pretty detailed maps I drew. The randomness came from flipping a coin. Incidentally, I knew how to flip coins in a way that looked random but produced the desired outcome. I know that cheating at solitaire is not exactly a sign of intelligence, but I wonder if the talent I developed to flip a coin and get what I wanted has something to do with this paper, where they recorded what happened in over 350,000 flips, confirming that fair coins tend to land on the same side they started. Anyway, as a kid, I flipped a lot of coins and drew a lot of maps, mostly of regions in Europe or around the Mediterranean. I can still draw decent maps on a white sheet.

Having drawn so many maps, it is not hard to make puzzles like the one on the right. It also provides some useless general knowledge. I guess that if you give me a map of Europe with dots representing 50–100 larger cities, and you give me the names of those cities, I can tell you which is which. Similarly, I think that, on a map where only borders are depicted, I could correctly fill in the names of all European countries. I guess the same is true about the Americas, at least if the dots just represent capitals. However, when it comes to Asia and Africa—mostly Africa—things are less rosy. My silly game invariably reenacted some history, and I suppose I always liked pretty Eurocentric history.

When I moved to the US, I was directly confronted with the limitations of my general knowledge, geographic and otherwise. It is not much of an exaggeration to say that when I arrived, I knew that both Los Angeles and San Francisco were somewhere on the West Coast, but I was not sure which one was further north. I did things like flying from Chicago to Salt Lake City via Phoenix. I guess it must have been cheaper than other options, but in Europe, I would have felt silly flying from Madrid to Hamburg via Helsinki. Ignorance is bliss, and I didn’t feel those qualms in the US. At least not at the beginning.

In the US, I also noticed my Eurocentrism in many other aspects. I always liked reading, but when I arrived, I learned about all those American writers who were completely off my radar. I went from an environment where I knew what other people knew to one where everyone knew things I had never heard of. I actually loved that feeling. It made everything interesting and new. The world was much bigger than I thought, and the feeling of abandoning European provincialism was exhilarating. But I suppose what really happened was that I just embedded myself in another form of provincialism. Let’s call it Westcentrism. Now I know where Ljubljana and Boise are.

As I already mentioned, besides drawing maps, I was always interested in history—random topics that changed over time. For example, I read quite a bit about the Byzantine Empire. When one does that, one evidently also reads about Persians, Arabs, and Turks: Sasanids, Umayyads, Abbasids, Ottomans, the whole lot. Now, the Byzantine Empire ended in 1453, and then this part of the world basically disappeared from the history I read until I got interested in the 19th–20th century. By then, these all-conquering people had mostly become the background of the history I was actually reading about. Still, I think I am decently informed about what happened during the last 100 years in the Middle East. I have an idea of who Ibn Saud, Nasser, and Mossadegh were. Besides that, I suppose that fiction and food, as well as knowing quite a few very smart and sophisticated people from around there—mostly Iranians—gives me a feeling of acquaintance with that region.

I suppose that’s why it was a shock when I was once invited to the house of a couple of Iranian friends, and she started showing pictures she had taken during a previous trip back home. There were amazing buildings, as expected. And what I would describe as Soviet-style buildings. That was already a bit surprising, although I had never spent a minute thinking about what kind of buildings they would have in Iran. I guess Soviet-style buildings were not what I had pictured, but that was fine. However, what was truly shocking were the pictures of a museum. I don’t remember which museum it was, but I think it was modern art. It might have been in Tehran. Or in Isfahan. I don’t remember. But what I really remember is the impression it made on me. It just looked like a very nice, very stylish, slightly minimalist museum. I was evidently not shocked by the picture itself, but rather by my inner surprise, as if my inner voice was telling me that there was something incongruent about such a museum existing in Iran. I mean, I was at the house of people I knew were much more sophisticated than me, from any point of view—definitely when it came to the appreciation of art. But still, there was something in me that made me feel that such a museum, in Iran, was unexpected. It was shocking because it was baseless. I directly interpreted my feelings as a form of Eurocentrism. Or Westcentrism. I recognized, through my reaction to that picture, how ingrained—without my being aware of it—was the feeling of European, or Western, superiority. I understood that, despite my MOMA-going friends, I looked at countries like Iran with the most orientalizing eyes. At the time, I tried to express what I felt, and she got pretty pissed at me. I still feel sorry for upsetting her. I still feel sorry for the whole incident.

Afterwards, I have sometimes taken tests to check how unconsciously biased I am with respect to race, religion, gender, you name it. These tests, like these from Harvard, ask you some generic questions, followed by some random ones, and then they make you choose between a bunch of things as fast as you can. I am not sure how they work, or if they work. But they invariably give the result that I seem to have some prejudices. Often slight, but always in the direction one would expect from somebody of my demographic. Since I think highly of myself, I am always a bit puzzled and kind of dismayed by these results. But by now, I have come to accept it as a fact, and I try—with unclear success—to be aware of my prejudices, to second-guess my opinions, to police what I think, to correct those biases. Using a pretty bad metaphor, it is a bit like knowing you are on a boat that tends to go windward, so you steer a bit leeward to keep it on keel.

Anyway, none of those tests, Harvard or not, had nearly the same effect on me as becoming aware of my surprise when I saw that picture of a museum in Iran. The incident with the picture happened a few years after the Iraq War, where we got to see a lot of pictures of the looted Iraq Museum in Baghdad. Those pictures on TV looked different from what my friends showed me. All the pictures we see from the Middle East condition us to think of it as something “other.” And that has an effect on oneself, even if one independently knows people who evidently don’t fit into that stereotype. And that effect has further effects. I remember being in a US airport when they were showing a documentary about the first Gulf War. They showed miles and miles of charred remains of trucks and tanks of the Iraqi army. Those trucks had been full of people who were all killed. One could only show all of that in an airport because those killed were “the other.” No way this would have been filmed like that if the people inside those trucks had come from Kansas. Or Auvergne. We might be horrified by what was done in Gaza, but in some sense, this is still happening to the other. I was in Chicago when, in 2004, some assholes bombed a bunch of commuter trains in Madrid. Reading the news, I cried in my office. I have not cried over all the news from Gaza. Or from many other places.

I am writing this as news spreads of a possible war in Iran, a couple of weeks after all those protests and the horrible ensuing repression. It seems that quite a few Iranians want to get rid of the regime there, and that if that means the US bombs, then that’s a price one pays. Instinctively, I would think that trusting Trump to solve one’s problems is a pretty bad idea. It seems dangerous to me. This article rings true to me. In any case, if it comes to bombing, one should remember that they have museums as nice, as stylish, and as little “oriental” as those anywhere near us. And that, if there are such museums, it is because people go there. Not the other. Just people. Just people like the ones who have you over for dinner at their place.