Investing

Everybody who knows me knows that I get totally obsessed by things, and that these things occupy a lot of space in my mind until something else tags along. The old obsession then fades away somehwat but does not really disappear. This is true about the kind of things I cook, the kind of books I read, the kind of math I do at any given moment. And for everything else as well. At some point, after years and years of basically not caring about it at all, I got obsessed with investing, or rather with what to do with the money one has saved.

Warning: this is a long post.

Why think about investing?

In life, there are much more interesting things than money, but if somebody told you that your salary was going to be increased by 20%, you would be delighted. If you won 100.000 EUR in the lottery, you would be delighted. In that sense, everybody agrees that money matters. At the same time nobody wants to be thought of trying to be like Scrooge, neither like Scrooge the duck, nor like Scrooge from A Christmas Carol, and for many people talking about money feels kind of dirty. And this is why people don’t talk about it. I didn’t learn anything about money when I was young, neither from school nor from my family. I hope to do a better job with my daughter, so that she can judge better what are her options, what are the really idiotic ideas, and what does make sense.

First off, why do I want money? Well, because at some point maybe I can use it in retirement, but what I actually want is to be able to help my daughter when she needs it. To be able to pay her to study somewhere. To take a year off and travel around the world if she wants. To be able to help her buy a house at some point. I also want money as a cushion for whatever happens. I want to have the money to adapt my house if somebody becomes an invalid. I think that all these are pretty non-Scroogy reasons to care about money.

I am not the only one who thinks that way. Altogether, people save a lot of money, going from 35% of their income in South Korea to under 5% in Japan, Australia or the US. But let’s talk about France. French households have a saving rate of 17-19% of their income. That was the average and, as everywhere, better-off households save more, but the median is still around 10-12%. In any case, that is an enormous amount of money. And to be clear, those numbers, at least for France, do not include mortgage payments on the principal residence. Nor do they include contributions to the rather generous state pension system. It is just the money that people could put under the mattress by the end of the month. According to the Banque de France, the French have 6.3 trillion Euros saved, about twice the GDP. An enormous amount of money. And most people never learn what to do with it.

So, what do the French do with their money?

The Banque de France does not include the under-the-mattress-savings into its numbers for the accumulated savings, but it is basically divided as follows:

- Cash: 12%

- Money funds: 49%

- Investment funds: 24%

- Pension funds: 8%

- Stocks: 5%

- Others: 2%

The investment and pension funds are a mix of money funds, stocks, and bonds, and it is thus not very transparent how these things are distributed. Anyways, when it comes to the amount regularly saved, over 80% goes to cash and money funds.

Why is this bollocks?

Let’s start with some school math. Suppose that something increases at a rate of p% a year. How many years does it take for it to double? In school you learn that what you need to calculate is the logarithm with base 1+p/100 of 2. You take a calculator, and that’s it. I know a lot of mathematicians and this is what they would do. But ask them to estimate, without a calculator, what the result will be, say for p=2, and they have no clue. They know that it is less than 50, but they don’t know how much smaller. And since the error is measured in years, it matters a lot because it makes it hard to evaluate different scenarios.

Here you have a trick, the rule of 72: If something grows by p% every year, then it takes 72/p years to double. Evidently, the rule of 72 is just an approximation, but if you apply it to real existing rates p, it works pretty well. Examples of the actual values versus the rule of 72 values, rounded to the closest integer.

- If p%=1%, then the actual value is 69 and 72-rule value is 72

- If p%=2%, then the actual value is 35 and 72-rule value is 36

- If p%=4%, then the actual value is 18 and 72-rule value is 18

- If p%=8%, then the actual value is 9 and 72-rule value is 9

- If p%=18%, then the actual value is 4 and 72-rule value is 4

So, let’s use the rule of 72 in a practical example: with an inflation of 2% a year (the ECB’s goal), if you keep your money under the matress, in 36 years you can buy half of what you can buy now. If you keep it for only 9 years, your money will have lost already 17% of its effective value. In 18 years your money would lose 30% of its effective value.

Now, keeping the money as cash in the bank, is equivalent to keeping it under the mattress.

Money funds are a bit better, because they give about the inflation rate, meaning that the effective value of your money is conserved. Well, besides the fact that nobody was giving you 10% interest in 2022, and that you pay fees to the bank. But okay, money funds are better.

Now, I don’t give financial advice to anybody, but personally I count with p%=6%, that is 4% over inflation. This means that I am counting with the effective value of my savings being doubled by the time I retire. And, to be clear, this calculation does not include future savings.

How realistic is this? How do you do that? Evidently, by investing in stocks.

Why are people afraid of stocks?

A lot of people are afraid of stocks because there are plenty of stocks, and they would not know what to pick. Neither do I, but you don’t need to know—more about that below.

A lot of people do not know how to invest in stocks. This is so because they have never done it: with the banking app in your phone, the one you use to see if you ran out of money by the 20th of the month, it takes 30 seconds to buy or sell stocks, having to press about as many buttons as to make a wire transfer.

People are also afraid of stock market crashes and such. That is very reasonable, but more about that later. People who already accept the idea of investing in stocks, are afraid of the market being too expensive, that there might be a bubble, and such. Also more about that later.

The morality of stocks.

Some people feel that stocks are “dirty”. That there is something wrong about trying to profit from the work of others. Well, I guess that in an ideal society where money does not exist and everybody’s needs are covered, I would agree. But this is not the real existing world, and if you ask me, it does not look likely that it will be. Anyways, in some sense these people must think that investing in stocks would make sense, because otherwise why would they feel moral discomfort at the idea of investing in stocks? And to these people I would say that, if it is not them who get the subconsciously asccepted advantages of investing in stocks, it will be somebody else who does not have the same moral qualms. In a nutshell, the effect of regular people not investing in stocks is that richer people get richer, and society gets even more unequal.

In any case, if you decide to invest in stocks you can avoid investing in things you don’t like: fossil fuel companies, weapons companies, mining companies, etc.

The case for stocks, in the aggregate.

Does investing in stocks at all make sense? Okay, why do companies exist? Evidently, to make a profit. Companies that don’t make a profit disappear, but in the agreggate, companies make a profit, and that profit goes to the people who put the capital. Why? Because otherwise nobody would risk any money creating a company. Creating a company is risky. More than 20% of companies fail within a year, and more than 50% within 5 years. So, companies have to give incentives for people to put money in them. And yes, a lot of bakeries fail, but you probably believe that there will be roughly the same amount of bakeries in France in 20 years, and this means that in the aggregate bakeries will have been profitable.

This Econ101 blah blah was there because owning a stock is nothing other than owning a bit of a company. Now, you can hardly go to the bakery in the corner and offer to buy part of their business, but that is exactly what you can do with stocks. If you open your app and buy a share of Bonduelle, you are buying some of the risk if Bonduelle opens a new factory in Corrèze, and you are buying some of their expected profits they get from selling cans of petits pois.

Companies traded in the stock market are different from bakeries in many respects. For example they are much more regulated, but a big difference is their size. That makes it much less likely that they will fail within a year, even if they make losses. Still, a lot of companies make no profit. For the larger ones it is unlikely that they completely disappear, but their value (the amount people are willing to pay for a share of the risk/promise of benefits) can become really small. On September 29, 2000, Apple lost more than 50% of its value. In a day. This means that investing in a company listed in the stock market is risky. And this means that investors must be given the expectation of profit to compensate them for that risk. And since you probably believe that in 20 years the stock market will still exist as a whole, it means that in the aggregate there is a positive expectation of profit. What is important here is the proviso “in the aggregate”, and more about that later.

Now, what is the expected profit from investing in stocks. Okay, if Bonduelle were to offer you the promise of 2% profit, there would be no way you would put money there, because that is what would would get from a money fund, without any of the risk. So, the promised profit of the stock market must be greater than what is called “the risk free rate”. The profit you get over the risk free rate is called the equity risk premium. (Actually, the risk free rate is that of state bonds, which is higher than what money funds give you, but let’s simplify things.)

How big is exactly the equity risk premium?

Evidently, nobody knows exactly what is the equity risk premium. Even if you knew that, it would make no sense to expect that individual stocks, or even stocks in the aggregate, would grow every single year by “safe rate + equity risk premium”. Purely logically, if this were the case there would be no risk and the equity risk premium would be 0.

In fact, at small scales of time, the stock market is pretty much random. Brownian motion was first observed by looking at how individual pollen particles move, but the first mathematical modeling was done in the context of the stock market, in 1900 by Bachelier. Indeed, at a first approximation, the stock market is Brownian motion. But with a drift, that is with the tendency to move up. Again in a first approximation, that tendency is the equity risk premium.

Now, playing blackjack once (with perfect strategy) is more or less a 50-50 kind of thing. However, you know that if you play it over and over again then you must expect to lose, because it is not 50-50 but 49.5-50.5 against you. That’s the drift. In the stock market, the drift is for you, and that means that while year-to-year the return is pretty random, on the long run it is positive.

Evidently, there are estimates about the equity risk premium of stocks. It varies from country to country, and over time. And nobody knows what it will be in the future. There are estimates that range between 3%-7%. In the period 1899-2022, the risk premium was 5.85% in the US, 4.56% in the UK, and 5.51% in the world taken together. Those numbers don´t include dividends, and the time frame includes the world wars, the fact that the Russian stock market went to 0 when the soviets took power, the great depression, the 2008 housing crash, and all. And these numbers are an underestimate because usually the equity risk premium is calculated with the secure rate being that of bonds, which give a greater return than money market funds. Anyways, an equity risk premium of 5% means that the expectation is that in 14 years you double your money in real terms.

When I say that I count with an investment return of 4% over inflation, that was my personal estimate of the equity risk premium minus a bit.

In the long run, we are all dead…

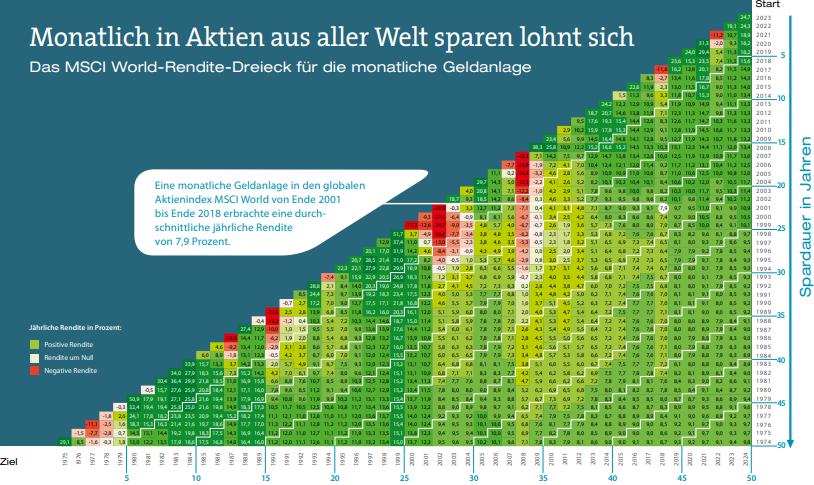

…Keynes said. With the Brownian motion picture in mind, the obvious fear is that it might take a long time for the drift to take effect. Okay, the following is taken from the Deutsches Aktieninstitut, where you get a better view.

The basic idea is that if you look at the (X,Y) tile you get the following information: if you invested in the MSCI World (a good proxy for the global stock market) at the end of year Y and kept it invested until the end of year X, then your yearly returns are given by the number you get. Green means positive and red means negative returns. There are bad years. If you bought at the end of 2007 and sold at the end 2008 you lost 42.2%. But if you waited a further year, you would have already made 7.1% a year. In some sense the worst time (in the 1975-2024) period to buy was 1999, when you had to wait for 5 years to break even. If you had waited until 2024 you would have still made 10% per year. A big crash like 2008 can mean that even if you were invested for a long time, you might be losing money: If you bought at the end of 1992 and sold at the end of 2008, you were just even. If you had, however, waited 5 years longer, you would have made a yearly profit (from 1992) of 6%.

This only says what it says, but the drift (in the period 1975-2024) is clear, and most of the time it does not take forever for it to dominate the noise.

The problem with this argument: implementation.

Maybe you agree that probably there is something like the equity-risk premium, and that it would be good to capture it. The problem is that you cannot buy a share of every company. Not even a share of every stock traded company. It might be easy to buy stocks using your phone, but a single Class A share of Berkshire Hathaway costs about 700.000 USD. Even if you decide that this is an outlier (it is: a share of Apple is about 270 USD today) you cannot really buy them all.

What you can do is sample. There are plenty of studies like this, suggesting that as few as 30, or even 10, stocks might be enough to sample. A problem with this is that if it is you who picks, you will pick companies you heard of, meaning that there will be a lot of bias.

A possible solution is to go to the bank and get somebody to buy things for you. This is what a mutual fund is. With the added benefit that you are getting an expert who knows the market and can buy something when it is cheap and sell when it is expensive. For this invaluable work the fund manager gets a cut of 1-2%.

That sounds nice and well, but there are two issues with that:

- With 2% fees, the equity risk premium is reduced from 5% to 3%, and that is real money: with 3% you money takes 24 years to double, against 14 with 5%. Said differently, after 24 years you return is reduced by 40%. The bank, or the fundmanager gets that money, with no risk for them.

- There are plenty of studies showing that randomly choosing sufficiently many stocks---one speaks of letting a monkey pick---and not paying fees, works much better than most fund managers. For you. Not for the fund manager. For them it works great whatever happens and whatever they pick.

How is this possible? At the end of the day you are paying to an expert whose job is to know the market. Well, that 5% equity risk premium is what the market gets in the agreggate. And now, what reason do you have to believe that your specific fund manager is average? I mean, if somebody should be very good, they would be inmediately hired by somebody else with more money than you and who can offer better conditions than you can. This means the at best you can expect your fund manager to be average once the good ones have been taken out of the pool. Besides, there are years when some fund managers do better than the market, but it seems a 50-50 thing with independent outcomes from year to year. Only 22% of US mutual funds have (even before fees) managed to get better returns than the overall US stock market. In a 10 year period it is just 10%. But they get paid their 1-2% fees. By you.

The consequence is that what one should just aim to get the average return of the market. It feels weird to not try to buy and sell smartly, but the logic is underpinned by the efficient markets hypothesis.

Efficient market hypothesis

The efficient market hypothesis says that the prices of financial assets reflect all available information. Every time one hears somebody playing with the words efficient and market, often ridiculizing the idea of efficient markets, they are referring to that. Markets are evidently not efficient. Still, when one understands it right, the efficient market hypothesis makes total sense. It is a brilliant insight.

Why? First, one should not understand the word “hypothesis” as in math, either something that one supposes true, almost like an axiom, or a statement that one believes to be true and that one can try to prove. It is rather a working hypothesis. A reasonable scenario into which to put oneself when one needs to take a decision.

Now, why does the efficient market hypothesis make sense as an escenario for you? Well, what is the alternative. That you, or somebody whom you pay, has better information than all the other people buying and selling stocks: if the majority knows that something is undervalued, then the majority would be trying to buy it, and the price would go up, and it would no longer be undervalued. So, if you think that one should buy this or that, you are implicitly assuming that you know more than others buying or selling stocks. This might be possible in some situations, but it is not something anybody I know believes. This means that people should be acting as if the efficient market hypothesis were right.

How do you buy the market?

Let us sum up where we are: by now one is maybe agreeing that, while the stock market moves up and down a bit like Brownian motion, on the long term there is a drift of about 5% over secure investments, and that the way of capturing it is to buy a share of the whole stock market, without paying fees and without trying to pick winners and losers.

But, how do you do that? The good news is that it is totally possible. The key is something called an exchange traded funds (ETF). They are nothing new—they exist since 1989—and in Europe there are about 2.400 billion Euros invested in them. That is one and a half times the GDP of Spain. You buy ETFs exactly as you would buy stocks.

There are incredible amounts of ETFs, some of them really weird, but the most important ones work as follows. First, the ETF provider comes up with a mathematical formula deciding how they are going to invest the money. There is nothing weird in such formulas. You know plenty of them. All the stock market indices they speak about in the news are such formulas: CAC40, SP500, FTSE100, IBEX35, DAX, NASDAQ100,… What are these indices? The SP500 basically is the following: take the value of the biggest 500 stock companies in the US, weighting each one of them according to their size. There are indices for everything. There are indices for the biggest European banks. For renewable energy companies. For all developed economies (e.g. the MSCI World of the triangle above). For developing countries (emerging markets). For the whole world including emerging markets. For large companies (large caps) or smaller ones (small caps). You name it.

Now, the ETF provider has chosen an index. When you buy a share of a given ETF, you and the provider are signing a contract saying that with your money they are going to buy stocks according to their formula, and that they will keep them whatever happens with the market. This kind of investing, not reacting to the fluctuations of the market, is called passive investing by contrast with active investing, that is trying to be smart and buy cheap and sell expensive.

A few points:

- ETFs, since they accumulate many small amounts, can actually buy all the shares needed to implement their formula.

- You own the actual shares, or the parts of actual shares you bought. This is not true for mutual funds. If the mutual funds provider collapses, you are done and dusted. If the ETF provider collapses, the shares are still there and are yours. Evidently, there could be fraud, but you are legally protected.

- Since following a mathematical formula is something a computer can do, and since the composition of indices does not really change that much from year to year, running an ETF is the cheapest thing possible. For many of the larger ETFs you pay fees of between 0.1-0.3%.

I am not a financial advisor, but it seems to me that a broad ETF, that is one based on a broad index, is the perfect way of capturing the equity risk premium.

How is it possible that this is not what people do?

Well, in the US these things are much more common and widespread than in Europe. So, many people do this. But not many people I know in Europe invest in ETFs. To me the reason is clear. Lack of financial literacy: not really having thought about the effect that a change of few percentages has for long term returns, not really understanding the point of stocks and being afraid of them, having the idea that people in banks know how to do things smartly (or even, that it is possible to be smart—efficient market hypothesis for you) and thinking that they themselves don’t know enough to invest in stocks, and just not knowing that one can buy the whole market.

I find it desparating, and this is why I write this.

How do you find ETFs?

In Europe, you can use justETF’s screener. The names look like “iShares Core S&P 500 UCITS ETF USD (Acc)”. Let’s look at that example:

- Let's start with some etymology: It is provided by iShares, Core is branding, S&P500 is the index it follows, UCITS says something about EU regulations, ETF is that it is an ETF, USD is that it is valued in US Dollars, and Acc means that it is "accumulating". About that more in a the next point.

- There are two kinds of ETFs, those which are accumulating and those which are distributing. It depends on what they do with the dividends from the stocks they own. The accumulating ones reinvest the dividends, and the distributing ones redistribute them to the inverstors (that's you). I guess that it depends on one's taste, but I have some vague reasons to prefer to accumulating ones myself. The distributing ones might be more psychologically soothing.

- Right next to the name there is a chart of what has happened in the last 4 weeks, and you can totally ignore that. Then there is the fund size. This one is enormous, more than 100.000 million Euros. The bigger it is, the easier it is to trade the ETF because the easier is to find a counterpart to buy/sell. I would be wary of picking an ETF with less than 500 million Euros in size, but what do I know?

- Next there is the TER (total expense ratio, that is the fees). In this case is 0.07%. Compare with the 1-2% of mutual funds.

- When you click on the name and go to "Basics" you find this all over again. There is however the word "Replication". It says "Physical(Full replication)". The "Physical" part means that they actually buy the shares from the index they follow, and "Full replication" is that they buy them all. They could also sample the index (they do that very well, but there can be a divergence). Then, instead of "physical" it could be "synthetic", where they just mimic the index with other shares. They also do that well, but again there could be a difference. The reason for the "synthetic ETFs" is that there can be some regulation saying that you have this or that advantage if you buy European shares (this happens in France for some things), and this means that they use European shares to synthetically mimic that American stock market. I only vaguely understand how they do that, but I am not really worried about it. Still, probably "physical" feels better. Personally, I would not care about the full replication or not.

- When you go to "Holdings", they tell you about the composition of their index.

- All of this you find together in the "Fact sheet". There, at the bottom you also find the "ticker", that is the acronym with which you search for them in the app in your phone. In this particular case it is "SXR8" if you buy in Xetra (German stock market), CSPX in the London Stock Exchange, or CSPX in Euronext Amsterdam. Not all ETFs are traded everywhere, and how much does your bank (broker) charge you for the transaction, that is what you pay in the moment of buying or selling, might depend on the stock market.

Random comments A few random comments to end, mostly about technicalities.

- Forced closure. Sometimes, because the provider decides to close the ETF, or because there is a regulatory change, an ETF gets closed. What that means is that the stocks get sold and the money distributed. This is a bit of bummer, but it is not tragic, and it does not seem to happen often.

- There are also super bizarre ETFs, with super strange indices. It is not uncommon for ETF to have individually made indices, but some are really weird. Keep the efficient market hypothesis in mind and run away from the weird stuff.

- Again with the efficient market hypothesis in mind, one should not be trying to sell and buy: why would you know better than the others? The key idea is: if you don't know better, and you don't, buy and hold.

- The prices of ETFs, that is the indices, fluctuate less than individual companies, but they fluctuate a lot. Keeping in mind the Brownian motion with drift idea, this is not very important if one is going to be there for the long run. But everybody says that what is important is to only risk what one is willing to tolerate.

- Actually, this fluctuations can play for you. A way to try to capture that, and to smooth the whole process is to regularly invest something, in a fixed ETF, whatever the price is. This is called dollar cost averaging.

- Again, the efficient market hypothesis tells you that you can't know if now it is a good moment or a bad moment to buy. And the Brownian motion with drift idea says that statistically it is best if you buy right now. This is kind of hard, because it feels risky. Something people suggest is to divide the amount in equal parts and buy at predetermined dates: make 4 parts and buy now, in 3 months, in 6 months and in 9 months. For one's mental health, one should also keep the image above in mind, as a representation of the fact that the in the long run, all of this doesn't matter that much, and that the long run is not that long.

- I believe that everything I wrote makes sense, and that is basically what I do myself. Still, contradicting my belief that one should work assuming that the efficient market hypothesis holds, I feel that the market right now (November 2025) is expensive. I might very well be wrong. Statistically, I will be proved to be wrong.

- One can also evidently invest in other things like bonds or real estate. I have considered it myself, and I didn't see the point. But I might very well be wrong again.

Anyways, at the end of the day, it is up to everybody to know what they do with their money. It is everybody’s risk and everybody’s possible profit. But it is silly not to think about it, and even more so not to know about it.